The Nuclear Weapons Sisterhood

It’s hard for women to be hired, promoted or taken seriously in the national security establishment.

By Carol Giacomo Ms. Giacomo is a member of the New York Times editorial board.

In the mid-1990s, Laura Holgate, then a senior Defense Department official, was in Moscow leading a delegation to discuss ways the United States could help the Russians secure plutonium from dismantled nuclear weapons.

After a male Russian official gave a confusing explanation about the Kremlin’s storage plans, she sought clarification. The Russian, his voice dripping with sarcasm, offered to “put this in terms a woman would understand” and then described loading plutonium into a “cooking pot and putting a lid on it.”

“I was so startled, I wasn’t really in a position to push back at that moment,” Ms. Holgate, now with the Nuclear Threat Initiative, told me in an interview. “It was incredibly disrespectful.”

For women, people of color and transgender people, sexism, discrimination and harassment are often barriers to being hired, promoted or taken seriously in the national security bureaucracy — overseas and at home.

While the numbers have improved in the Foreign Service, where women hold about 40 percent of all officer jobs, and the State Department, where 40 percent of the senior posts are held by women, they hold only 20 percent of senior civilian jobs at the Pentagon.

Women are particularly underrepresented in senior positions dealing with nuclear issues, according to a study by New America, part of a growing effort involving various groups and individuals to make the fields more welcoming to women.

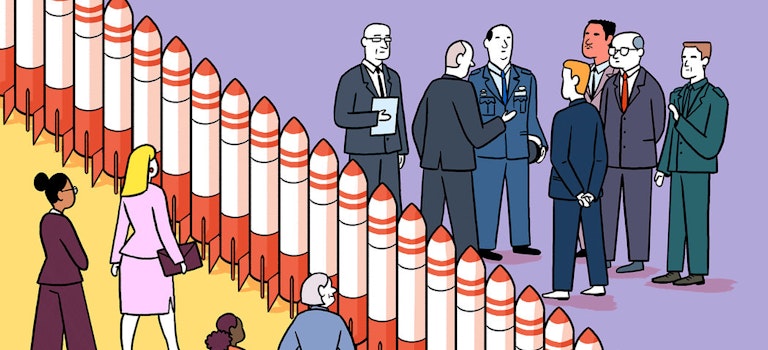

Part of the problem is the discipline itself, the study found. Policies involving the building, deployment, targeting and use of nuclear weapons have long been the province of an insular, innovation-averse group of men. Discussions by this “priesthood” conflate national security and manliness with sexualized jargon about vertical erector launchers and thrust-to-weight ratios. The demand for nuclear orthodoxy has excluded outsiders, particularly women, placing them in a “consensual straitjacket” of conformity in a male-dominated world.

Just consider Donald Regan, the former White House chief of staff, who before President Ronald Reagan's summit with Mikhail Gorbachev in 1987 said women were “not going to understand throw-weights” or other national security issues raised at the meeting.

The numbers show how this order became so entrenched. From the 1970s to 2019, the study found, women held 11 of 68 of senior positions dealing with nuclear weapons, arms control and nonproliferation at the State Department, 13 of 109 of these jobs at the now-defunct Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, five of 63 at the Defense Department, five of 36 at the Energy Department and two of 21 national security adviser positions.

Generally, women have been more welcomed in offices involved with arms control and nonproliferation, which center on negotiating limits on weapons rather than developing or using them.

Even so, to be successful in these posts so critical to national security, women pay a “gender tax,” performing “the constant mental and emotional calculus that comes with implicit sexism; explicit sexism and discrimination; gender and sexual harassment; and gendered expectations,” according to the New America study, based on interviews with 23 women who held senior government positions.

Nearly all of the 23 said they were harassed or saw others harassed, and when a foreign official was involved, the stress was magnified because it could cause an international incident.

During a round-table discussion with Global Politico in 2017, Laura Rosenberger, who spent 11 years at the State Department and the National Security Council, talked about wearing more pantsuits and baggier tops as a defense mechanism “to make myself seem less attractive in the workplace.”

Mieke Eoyang, who served 12 years as a staff member on the House Armed Services Committee and the House Intelligence Committee, has described how she would walk into a meeting and be asked to get coffee or how a committee chairman cornered her at a reception to discuss his sexual prowess.

Michèle Flournoy, a former senior Pentagon official who was expected to be the first female defense secretary if Hillary Clinton had won the presidency, told me she was fortunate enough to have supportive, often male, mentors and to have risen quickly in the field. She was, hence, less vulnerable to sexism and discrimination. But she has won plaudits as an inspiring leader who helps younger women advance.

Ms. Holgate predicts even greater strides for the next generation. There is a new vocabulary for identifying discriminating behavior — men-only expert panels are now mocked as “manels,” for instance — and more men are standing up for their female colleagues, she said.

To encourage progress, Pamela Hamamoto, who served as United States ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva, began a program called Gender Champions to identify international leaders committed to advancing women, and Ms. Holgate, a former United States ambassador to the United Nations in Vienna, replicated it in the United States.

But does having women at the table really make a difference? There is little evidence women are inherently more peaceful than men. A forthcoming paper by Alexandra Stark of the Belfer Center at Harvard’s Kennedy School and Madison Schramm of the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, goes so far as to argue that, in certain parliamentary democracies, women leaders, feeling a need to prove their strength, “may be more likely to initiate conflict than their male peers.”

But the New America report found that including women in nuclear decision-making makes discussions more collegial and encourages collaboration and innovation. Could this subvert the orthodox notions of nuclear planning? Other research suggests a more diverse work force produces better results and that risk-taking behavior may be greater when women are not involved in decisions.

Fairness and good sense argue for greater inclusion of women and underrepresented groups in all crucial policy fields. No democracy can afford to exclude so many talented people from fundamental decisions of war and peace.